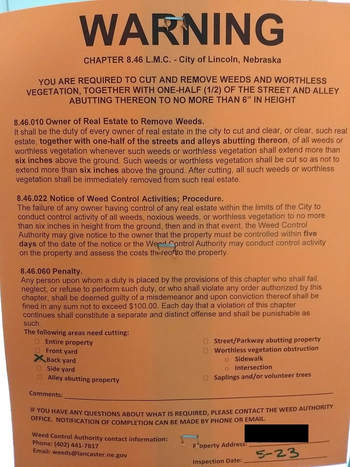

But here's the top mistake, or at least the one I'm feeling today -- mismatched planting. Specifically using plants that get too tall.

In a traditional garden border tall plants go in the back with tiers coming forward where groundcovers eventually dominate the edge. Now, this style can still be done with native plant landscapes (although we'd prefer a more ecological approach), but too often a "native plant landscape" appears to give folks a cart blanche to just plant whatever wherever.

I think of Ratibida pinnata, grey-headed coneflower, as a prime example. Out in its natural habitat of the tallgrass prairie this pioneer species often has big bluestem and indian grass to lean on, but bring it into a garden bed and it's treated like a specimen often marooned in wood mulch around shorter plants. You bet it's going to look out of place. One strategy is to surround it with other tall forbs to support it, but then you've created a garden of 4-6' tall plants -- and if this bed is in your front yard it's going to look overgrown to a lot of people with more traditional expectations. And just wait until the tall plants start leaning for the best light. With less competition in a manicured garden, plants like R. pinnata will be in heaven -- that's why we need to consider mimicking how plants grow and compete together naturally in more difficult circumstances.

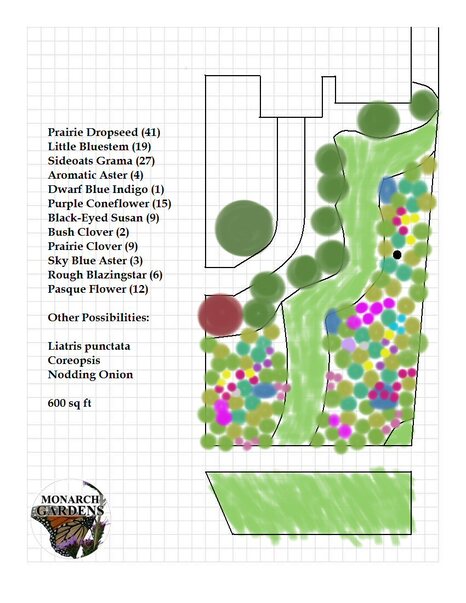

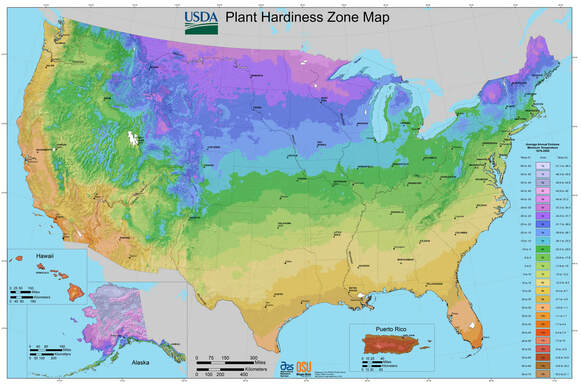

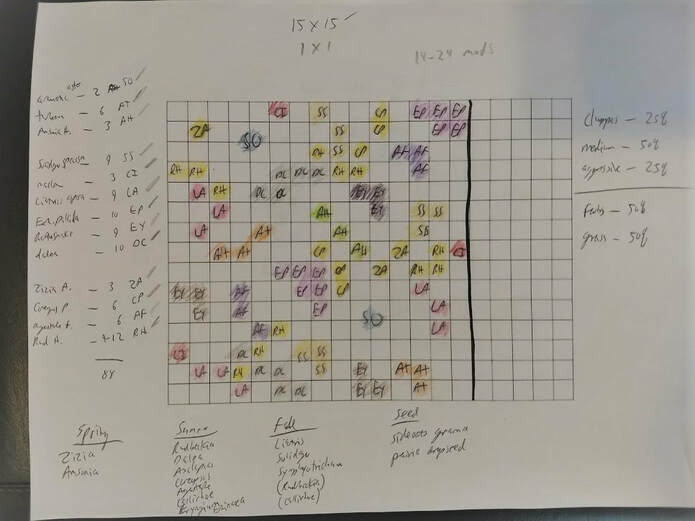

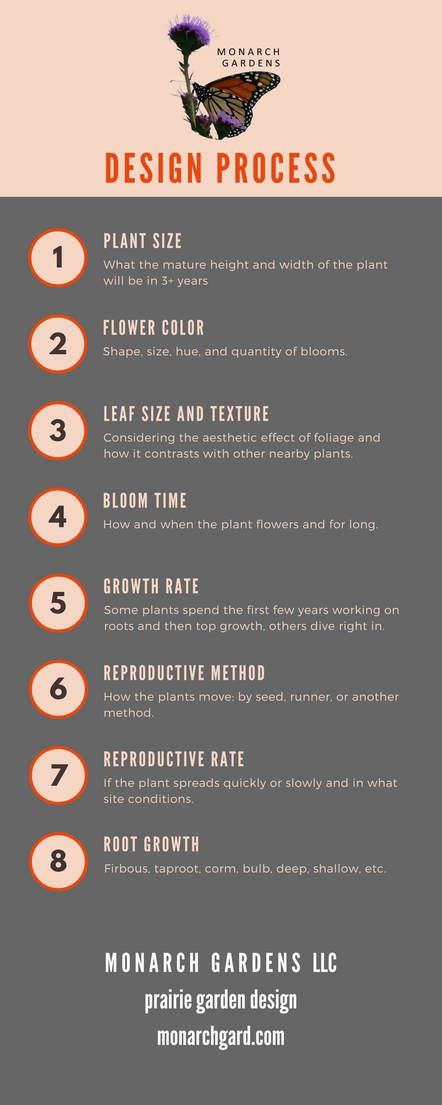

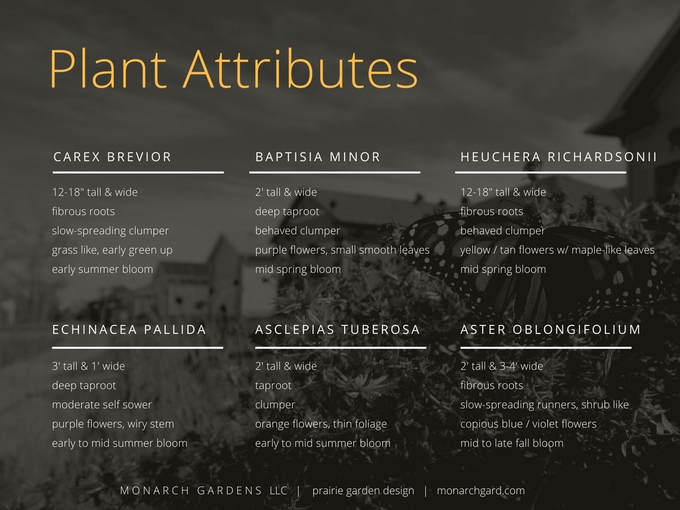

At the heart here is choosing plants that have similar growth styles (shape, robustness, spread) and that intermingle to cover the ground. If the average height of these plants is 18-24" then you can go in and add a taller Liatris aspera or Eryngium yuccifolium for a pop of architectural je ne sais quoi. And perhaps an ancillary angle to this topic is -- at least at first -- limiting plant species especially in smaller beds so as not to visually overwhelm the space, adding diversity as you go along in the years and learn how the plants grow. Every garden is different.

What do you think? What has your experience been when bringing "wild" plants into the urban / suburban garden?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed