From the Gulf Coast of TX and LA, to the Palouse of WA and OR, the Great Basin desert step of UT and ID, large chunks of CA, the Mescalero Sandsheet of southeastern NM, and the Piedmont of VA, NC, SC, and GA, not to mention others like the longleaf pine savannas of FL, SC, AL, MS, LA, TX, or meadow remnants in TN and AR. Prairie is everywhere, not just in the center of the country.

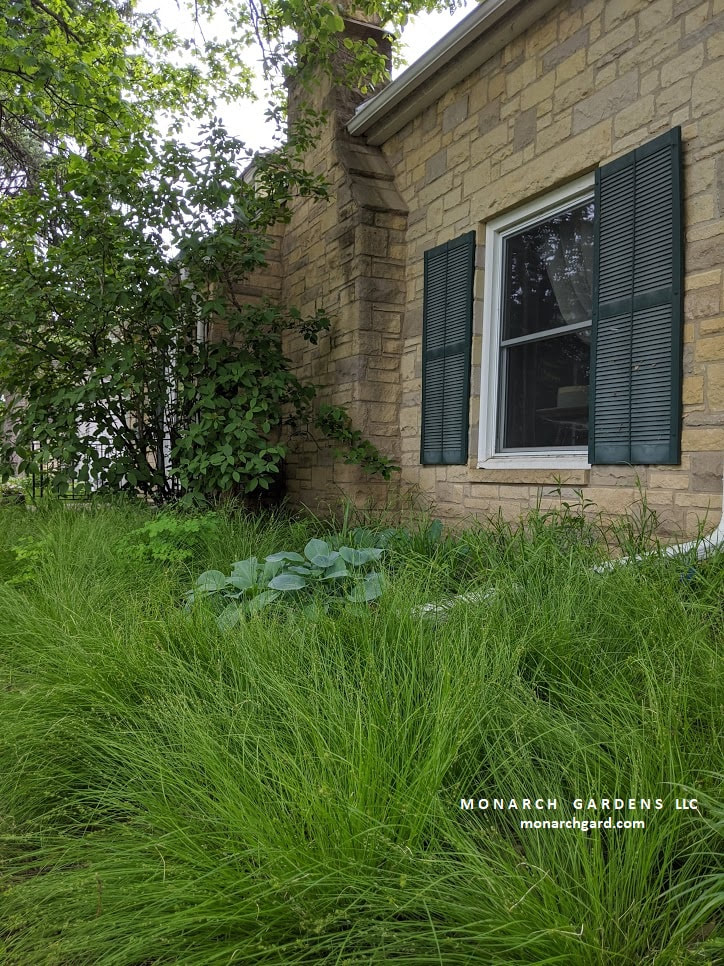

As disturbed landscapes heal themselves, prairie / meadow is often the first stage of restoring ecosystem function; we can use principles from this natural succession in ecological garden design by first planting prairie and meadow plants that, over time, give way to a more woody or open canopy forest structure (if that is actually the late-succession / climax stage of your area). This succession rebuilds and heals the soil, increases water infiltration, and out competes weeds among a cadre of benefits. If you are converting from lawn -- even if you live in Maine -- the first step is likely a meadow.

These ideas form the fundamental approach of my forthcoming book, Prairie Up: An Introduction to Natural Garden Design (spring 2022), and are explored more in depth through online courses. Ultimately, what we can learn from one another across the country when it comes to sustainable and resilient garden design far outstrips what makes our gardens different. The things I've learned from southwest gardeners concerning drought tolerant landscapes is profound, just as I learn from conservationists in the southeast about the differences and similarities of their endemic grasslands and their struggle to reclaim ecological heritage.

Chances are, if you stop to research your ecoregion and locale, you'll find a prairie remnant that can teach you much about how to rebuild ecosystem function and habitat in your highly-disturbed home landscape. From lawn to meadow, from meadow to open woodland, from open woodland to forest, we can easily deliver habitat connectivity where we live while helping species adapt in a time of human supremacy and climate change.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed