So the very difficult task for wildlife and natural gardeners is to try and create a bridge between the common expectations of what a yard or garden should look like (and where it should be), and the fairly recent expectations (1950s) that a lawn makes you a team player in the parkification of suburbia (oh just you wait until my forthcoming Kill Your Lawn presentation -- the newsletter lands Saturday and will fill you in).

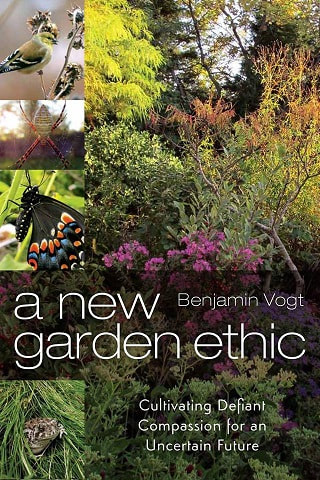

In books and lectures and classes and pocket guides, I've worked hard to try and lay out what that bridge looks like and how to cultivate it. Strangely, the below bullet points of that bridge have also led to a sort of fracas between wildlife gardeners and garden designers -- we are great at dividing ourselves as a species, but that's another topic entirely (maybe one embedded in A New Garden Ethic which is now in its fourth printing). But if we're not employing commonsense design and management principles into natural spaces -- using elements of design accepted by folks unfamiliar with natural design and thus afraid / dismissive / upset by it -- we're simply adding to the problem. A totally wild, unkempt, cacophony of lawn-to-meadow conversion is a lost opportunity, and indeed, shooting ourselves in the foot.

So what are some guiding principles for a more natural, front-yard lawn conversion that, in a few small ways (that admittedly often feel feeble and fruitless), extends an olive branch to the monoculture, resource-intensive, dominant suburban culture?

- A limited plant palate based on square footage. The smaller the space, the smaller the species list should be so as not to visually overwhelm.

- A cohesive, single-hued green base layer, groundcover, or matrix which ties the space together like a lawn might. This is color theory 101.

- Always have 1-3 forb species in bloom at one time -- and no more. Again, the smaller the space the more this is important.

- No herbaceous perennial or annual plants taller than 3-4 feet.

- Taller plants in the middle or back of beds. Nothing tall within 4' of the sidewalk.

- Employ cues to care that help show intention and access: paths, benches, sculpture, bird bath, arbors, metal edging, a sign, etc.

- Don't use aggressive species. Research your plants to carefully match the site AND one another in the larger plant community.

- Arrange seasonal flowering plants in repeating masses and drifts. Repetition is pleasing to the eye and helps show cohesion. Massing also creates a bigger beacon and reduces energy expenditure for pollinators.

It is disheartening to to see images of front yards, touted as liberation for wildlife and from the tyranny of our monocultures, without any eye toward design or accessibility that would be more welcoming to others. Again, ANY landscape that isn't clipped lawn will be an affront, but we have to do better as advocates for change. None of the above bullet points will reduce the ecosystem services we urge for as wildlife gardeners conscious of climate change and mass extinction. However, just letting plants ramble about, get tall, flop into sidewalks -- and appear totally disheveled and out of control while blocking sight lines -- is a detriment to what we hope to achieve as we work for equity among all species by encouraging neighbors to rethink lawn monocultures.

Soon enough water restrictions will force the issue, especially in the west and Plains where we're writing to you from. At some point -- even our local weed control officials admit -- we won't be able to have the traditional lawns we have now.

In the meantime, it behooves us to design AND MANAGE spaces with intention, knowing the plants and tending the space as a new kind of gardener -- not a gardener who applies herbicides or annual mulch applications or fertilizers that pollute waterways, but a gardener who learns plants and maintains a sensible balance of design and activism for a healthier future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed